Atlanta's Portrait of Black Men and Tropes

An exposition of what many Black boys and men feel, but never becomes validated. Just because the show has ended doesn’t mean the conversation should die too.

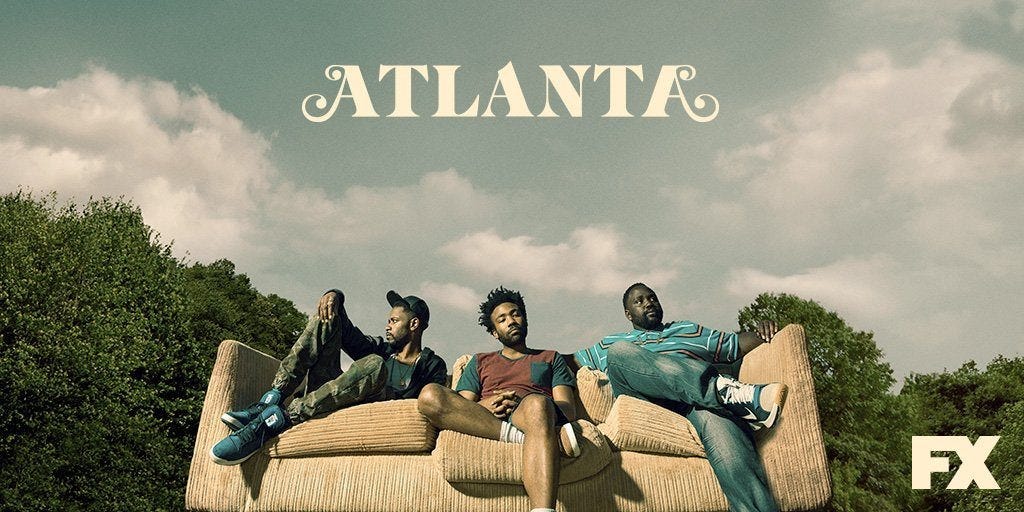

Donald Glover’s show, Atlanta, is docked as a comedic drama despite dark satire. If you angle it right, there’s a way to provoke humor out of the mundane lives of these Black characters. It’s a space familiar to Black individuals living in predominantly Black neighborhoods, articulated through abstract metaphors.

One of Atlanta's crucial questions throughout the series is: what happened to Earn and his enrollment at Princeton University? This question is asked in the first episode with Earn’s intellect thrown back in his face. He is supposed to be a genius, yet he’s here in Atlanta struggling to survive and stuck with a boring minimum wage job.

Earn’s cousin, Al (Alfred), is the one to ask in this first episode, following up his confusion by expressing that he “no longer feels that [he] knows Earn anymore.”

The writers of Atlanta decide to withhold this truth until the beginning of season four, the last season. Denying the audience's ability to reduce Earn to a bad moment, the same way everyone around him does. Or like Sasha could.

Withholding information gives Earn his second chance. This isn’t a ‘no tolerance environment’ seeking to punish and criminalize. He isn't a character made completely vulnerable. Not yet. The audience must earn this right and first go on a journey with him.

Throughout his journey, it’s unclear who knows the truth about why Earn got expelled from Princeton. The audience only sees how the people around Earn tolerate his behavior.

Everyone marks Earn’s success by his ability to get into an Ivy League college. He’s supposed to get a degree, have a career that’s good enough to keep him out the hood. He was never supposed to return to Atlanta.

His parents don’t offer him warm greetings or invite him inside their house. They limit their interactions with their son to cold speech and action.

The diligence of “supposing” pushes the narrative of a virulent environment where Earn is frequently dis-positioned. He is sitting in his awkwardness alone.

At home, he is supposed to defy stereotypes despite the street culture that surrounds and influences him. Otherwise, he is another Black man who cannot make much of himself.

At school, he is supposed to be a great example of how Black people can succeed. That they can be a part of a society that isn’t conventional to who they are and finally deemed as worthy.

Suppositions produce insecurities that are internalized, projected, and acted upon.

Al shares that with Earn’s potential, he expected Earn to leave him behind. Therefore, it’s unexpected when Earn returns and begs to be Al’s manager for his public persona: Paper Boi the rapper.

No one is inescapable from becoming a product of the environment they grew up in. What matters is how the individual shapes their existence as an individual.

Like most Black men, he exhibits a feeling that he is unsure how to unpack. He needs the space to unravel what his feelings are exactly about his current status of financially struggling and what it means to him and how this defines him.

For the first three seasons, no one knows Earn’s intentions. Earn is reminded that he’s moving through his life like a piece of wood floating still in open water.

Yes, Earn’s goal of becoming a successful entrepreneur is made apparent. However, he pushes the narrative so hard that he’s willing to sacrifice so much of himself to be validated as a success story. But no one understands why he suddenly changed his career path? Why is he diving into a freelance path of instability and uncertainty?

—

There’s a culture of dependency on the rap scene, as it’s viewed as the thing with the potential to make it out of the hood for these men. Black men tend to be more accepted as rappers than they are on any other career path or as a student attending an Ivy League.

Rap is an accessible outlet for the Black boy to express their traumas. This includes talking about drugs and violence. Rap music can sometimes be musically relatable for some, but mostly it’s viewed as entertaining for the general audience.

For Paper Boi, the reality is he lives in the hood of Atlanta. In order to survive, he sells drugs because, unlike Earn, he doesn’t see himself with a skill with the same potential to take him out the hood besides rap.

He doesn’t want it publicly known that he sells drugs, therefore, he’s in constant friction with avoiding characterizations attached to the rapper aesthetic. This part of himself is something private and impersonal. It does not reveal who he is.

Drugs, guns, club scenes, etc., produce images and suggest that he condones these behaviors, yet he only does it for his survival. It’s not something he wants to do or enjoys.

“You know being a rapper is something a kid in high school wants to do.”

It’s perceived as an immature and underdeveloped choice. Leaning on Black men as rappers becomes an immature trope to want or expect. A subtle nudge to the mental process of leaning on a system that gives Black boys a platform to assert themselves. However, this further exploits Black boys and men to violence.

Around the 1980s, rap transitioned into a genre that reflects street life and gang culture. Men who were exposed to gang culture and narrated their experiences through rap also pushed norms about how Black boys are supposed to use assertion of self to ultimately identify themselves.

Otherwise, who else are they supposed to be? It’s made to seem that they are born into something political and institutional beyond them. When the odds are stacked against them, when most expect the worst of them, this repeated narrative is all they are meant to be.

Rarely are Black boys allowed to articulate their feelings in healthy ways. Preventing them from regulating their lives and embracing their existence as individuals.

The immaturity of this trope targets Earn’s emotional intelligence. To him, being the manager of a rapper is the only accessible chance he gets. He only wants another chance.

Episode 1x1 “The Big Bang”

The episode that defines and shapes Atlanta’s thematics.

The Big Bang — a dense point of energy where an explosion occurred. An unimaginable force that led to the development of matter which created the galaxy, and ultimately, the entire universe.

The intensity of the show and its surrealism is established in the aftermath that led to Earn being kicked out of Princeton.

Immediately, the pilot begins with an out-of-context scene. From the outsider, the scene appears as two Black men in a parking lot arguing and being aggressive towards one another. An ego trip, maybe? The argument ends with extremes: a shootout.

The visual of the scene wants the audience to fall into their familiarity, feeling that they know how to comprehend the characters exhibited in the scene. It’s a visual that assumes that these men are “thugs” involved in street life tensions and producing a hyper-violent space.

Looks like a dispute between gang members, doesn’t it? Or is this your supposition?

Meanwhile, Earn is positioned in the middle of the two arguing, trying to diffuse the heat of the moment. When talking to the other guy, he slips into a standard American dialect. When he’s addressing his cousin, he slips into African American Vernacular English (AAVE).

Standard American Dialect — the voice often listened to and heard. Often characterized by the phonetics and linguistic character of white Americans and deemed the correct way to speak. It’s the dialect taught in schools. Naming a proper way to speak frequently ignores the diversity of America’s regions. There is an unwillingness to include linguistic languages.

AAVE Dialect–the voice is often alienated. The dialect is not understood outside of Black communities as a grammatically correct way to speak. AAVE is associated with the idea that its speaker is uneducated, rather than recognized for its origin.

Earn flips between the two phonetics, wanting to adapt and survive the moment in the effective way he can. He wants to be personable when addressing Al, but also a general voice of reason to the other guy Earn is unfamiliar with. The balance of dialects at this moment borders on concepts of who is perceived as authoritative. For Earn, the moment is about proving he “can play both sides if needed.”

This moment reveals Earn’s willingness to enter different spaces and ground himself within them. The code switching is a potential effort to gain something outside from the hood.

This scene is abandoned as the rest of the episode is spent world building. It isn’t until the end that the audience returns to this first scene. We then learn more about what led to the opening scene.

Al, Darius, and Earn were sitting in the car listening to Paper Boi’s song. It was his first time on the radio. A random guy came by and intentionally broke Al’s side mirror. Al got out of the car, wanting the guy to give him money for the mirror he broke. The guy refused.

The episode began with a trope. It isn’t until the end of the episode that the original aesthetic is validated and understood. The audience is allowed to know what happened, what went wrong, and why.

The episode ends with not only a broadcast of the shooting, but the exploitation of Paper Boi and Earn Marks. Their pictures are plastered on TV in a specific way.

Paper Boi is pictured outside holding two bricks of drugs. In this narrative, Alfred Miles’ identity is hidden whereas Paper Boi’s is prominent.

Earn Marks isn’t easily distorted. The picture obtained and presented mimics a school picture. Although they exploit his character, the truth of his life is inescapable.

Throughout the show, there are small moments that are familiar, predominantly to the Black audience. We know how this plays out, yet the character’s actions repeatedly deny these tropes. Atlanta’s characters often remain authentic to their own emotions and what they feel is right.

But this scene is not a convention for you to exploit.

We have now entered a false sense of reality.

Earn’s Passiveness Towards His Relationship With Vanessa (Van)

A relationship is personal. Earn continuously returns to Van yet he isn’t intentional nor allows himself to express nor pinpoint what this relationship means to him.

He stays at her place, emotionally dismissive, has her pick him up from hooking up with another woman, and never wants to compromise. Most of their issues are not about whether he is a good father to their daughter. It’s about how he constantly fails Van.

They’re trapped in a cycle of Earn wanting to be with Van, but never making himself emotionally available or showing genuine affection. Often he remarks that once he gets his money together, he can afford to organize and make things right in their relationship.

But affordability is both an actuality and a reluctancy. Van is waiting for Earn to show that he loves her and appreciates her as a person. She constantly sits with confusion about why he wants a relationship with her, but recognizes how he cannot answer questions about his own intention for himself.

Van: “What do you want?”

Earn: “I don’t know, I guess I just want a chance to find out. Who doesn’t?”

The Manager Complex

Earn is asking Al to allow him to be his manager, defines everything Earn wants to embody and convinces himself to be. The approach is based on self-interest.

A manager is someone who makes things happen. Someone who protects the brand. Someone confident, a natural leader, and who can handle pressure. Managers are characterized by responsibility, transparency, accountability, consistency, and trust.

For Earn, being a manager means finally achieving a goal that pushes him out of a stereotype.

It’s an underlying desire. (The thing that brings him out of his nothingness.) Earn shows that he has the leadership and agency to be a manager, to advocate for his artists, but this well-developed side of himself is purely business.

Al asks, “Do you know what manager means?” Earns offers a technical answer, which Al rebuttals with a more social definition. “Manage comes from the word man, and that ain’t really your lane. I need Malcom and you too Martin.”–A hint to a man with power in his speech but can also dip his hands in the dirty work that the street life requires for survival.

To Earn, the manager position means he can finally get a handle on his life.

—

4x2 “The Homeliest Little Horse”

A moment to dive into Earn’s psyche. To reveal the situation that brought Earn into his life in the Atlanta universe.

By season 4, he has that financial stability and success status that he’s been chasing. It’s a point where he has no other choice but to face himself, the self he’s denied honesty and emotional nurture for years.

He’s spent so much time marking his self-worth through an ideal lens believing otherwise, he wouldn’t be respected. What did he lose to himself? What did he deny himself? How does immaturity reveal itself?

After all the turmoil of the past three seasons, Earn decides to go to therapy. What seems pointless at first becomes a moment to “find out why [because] the time is right.”

Earn’s therapy session begins with his therapist asking him about who he trusts. We learn trust is the main thing broken within Earn that has led to lack of trust in the world he lives in and the people he often surrounds.

What happened to Princeton was a failed trust in friendship between Sasha and Earn.

Both Sasha and Earn were RAs in the same dormitories. They developed a good friendship, which Earn believed involved trust between the pair.

When Earn gets a job interview, he gets himself a stylish suit to make an impression. While in the library, with his suit, a girl he was crushing on invites him to attend a party in Philly with her. Earn wants to but is conflicted about where to store his suit. Sasha, who overhears, offers to store the suit in her room so he can return to campus the next morning, grab it, and go to the interview from there.

The following day, Earn goes to grab his suit. Sasha isn’t around nor responding to his texts or calls. Once she does, a bit after the appointment time of the interview, she informs Earn that she isn’t around. Earn, who is panicking about missing the interview, makes the choice to use his master key to go into her room and grab his suit. He takes the suit, then leaves.

His intentions are purely to get this new suit and not miss this job opportunity. His intentions are pure until the moment it isn’t.

Sasha is upset with Earn’s choice. She reports him to the dean and makes the situation into something it never was. The Princeton administration “started using rapists' language for what I did...intruder…personal assault…attack of privacy.”

Earn learns the hard way that their friendship cannot go beyond Sasha’s victim mentality. She believes that the Black man truly acts to be invasive, predatory, and violent.

An apology at this moment is not enough. The view from above is “this big black gorilla came into this white girl’s room and just destroyed [her] shit.” Sasha, someone Earn trusted, reduces him to stereotypes and in this process, refuses to understand why he felt it was okay to enter her room or if he did anything else. It is not up for discussion between the two. It is a matter of all the terrible things he could have done rather than the facts.

The circumstantial conspiracy becomes believed.

Earn points at the performative behavior from the university. They gave him the RA position, along with a master key, trusting him to use it ethically. The act of giving him the key and easily taking his status of RA from him speaks to morally switching back and forth.

Should he have rights to the master key or not? Is he only there to contribute to the diversity claim? Were they waiting for the opportunity to say that he was unworthy of being a student at an Ivy League university?

Earn reveals that after the accusation “everybody was talking about me. I’m like one of twelve Black kids. You know I already felt alone.”

Due to the alienation of his experience, he is held to a higher standard. In theory, Earn represents an inclusion point for Princeton. Mistakes cannot be afforded. He is in the spotlight and the administration office doesn’t want potentially bad press attached to their institution.

One strike and he’s out. There are no attempts to distinguish new coherent boundaries between Sasha and Earn. Their relationship is diminished.

Earn was ignored and invalidated. The handling of the situation refused to consider Earn’s side or find a motive. The assumption is made into a belief.

The spotlight theory is confirmed years later when Princeton reaches out to Earn, knowing of his newfound success as a manager, asking him to publicly receive an honorary award. They want to brand him as a product from Princeton despite kicking him out. They want his value, not his humanity. They don’t offer forgiveness or any opportunity or a degree. It’s performative.

After retelling the story, for the first time, the audience witnesses Earn cry. He allows himself to feel all that has emotionally built up within himself over time.

After a couple therapy sessions, Earn recognizes how, after getting expelled from Princeton, he has spent so much time trying to prove that he could be a worthy, successful man. All this desire stems from his anger of being reduced to a stereotype.

He knows the trope he’s pinned to and spent so much time letting this consume him so that he may reject every ounce of this stereotyped character.

“I trust people to be themselves. Based on their incentives and what they’ve rationalized.” - Earn Marks

The Chase of Spite & Powerlessness

Once Earn unveils his story, he feels powerless. Similar to the way he felt powerless in the accusation and during the expulsion decision.

Earn states: “I love spite. It’s a pure powerful thing. It gave me courage. You know I can count on it. I used it when I came back to Atlanta.”

A toxic moral that brings out a sinister side of Earn.

Instead of processing his emotions, he holds on to them, lets the anger bottle up inside him, and allows his anger to turn into spite. What the audience witnesses are the depths of his spite, leading to a need to prove a point.

Spite is the tool Earn uses to destroy Lisa Mann’s life. Lisa Mahn is an airport worker who racially profiles Earn at the airport, messing up his family trip.

In spite, he pays someone to research more about Lisa. He learns of Lisa’s long-term career goal of becoming a successful author. A literary agent is hired by Earn to contact Lisa regarding the possibility of publishing her children’s book, The Homeliest Little Horse.

The literary agent gets into Lisa’s head, projecting that her story will become as popular as The Berenstain Bears. Lisa quits her job in pursuit of this opportunity. On live TV, Lisa reads her book at a local library to a group of “mostly inner-city kids,” where she receives negative reactions.

The kids found the story stupid and boring. Lisa loses her publishing opportunity. Lisa also goes into debt.

Everyone contributing to the narrative that Lisa is an excellent author were paid actors. Yes, this was all coordinated to hurt one person. Even after therapy, Earn laughs about the whole thing. It isn’t until Darius states, “I can't tell if this is extreme, extreme pettiness or terrorism,” that he questions his actions.

Therapist — “Spite can be very powerful. But it can also leave you depressed and empty. Goals stop becoming yours. Start becoming a book written by someone else. Someone with no incentive for your well being. So by not going back to Princeton you may be proving something to her and not yourself.”

Spite is the fuel that removes a character from their persona. It’s shallow and aims to spread hurt by reproducing hurt rather than addressing it and treating it as the wound that it is.

—

“Us Humans are always close to destruction.”

It is to say that people are not destruction itself, but always close to its proximity.